Around July this year, I decided to quit video games until my novel was finished. I had been struggling with procrastination and I thought setting aside my 3DS and the various titles on my laptop would help give me the focus I needed to push through to the bitter end.

But no. Addiction is a tenacious little monkey, and the locus of my timewasting simply jumped the species barrier from electronic to actual, tangible games. For the past few months, I have been playing boardgames.

So now we find ourselves staring down the barrel of Christmas, traditionally the season when those of us who don’t even like boardgames end up playing them as a means of passing the endless, otherwise-unmediated hours of contact with family and loved ones. If you’re anything like me, this may be one of the only times in which those few boardgame boxes come down from the shelf, crusted in a grey, feathery layer of dead skin, looking about as inviting as a moist bin liner full of medical waste.

I’m not about to mount a defence of the Christmas games you’ve learned to hate. Your antipathy is understandable. They are shit. Perhaps, you conclude, you’re just not a games person.

And that’s possible. I don’t think there’s anything more likely to confirm someone’s suspicion that they don’t enjoy games than trying to chivvy them into playing against their polite refusals. Boardgames are just an excuse to spend memorable time with people you love, and if you can achieve that rewatching a favourite movie or slathering your naked bodies in cocoa butter, putting whalesong on Spotify and turning the dimmer switch down to a seemly crepuscular hue then I would be a Grinch indeed to stop you. But – but but but – many of the games that have been most popular in Britain over the last 30 years have also been some of the shittest. A sizeable revolution has taken place in boardgames over the last decade, one that most people don’t know about, because boardgames don’t really have an outreach programme, and so families are still joylessly handing down Monopoly from generation to generation, tragically unaware that there is a better way.

Quite a few people, aware of my sickness, have asked me for boardgame recommendations for the imminent festive season. Here are my suggestions for games to burn, laughing, and what you should replace them with.

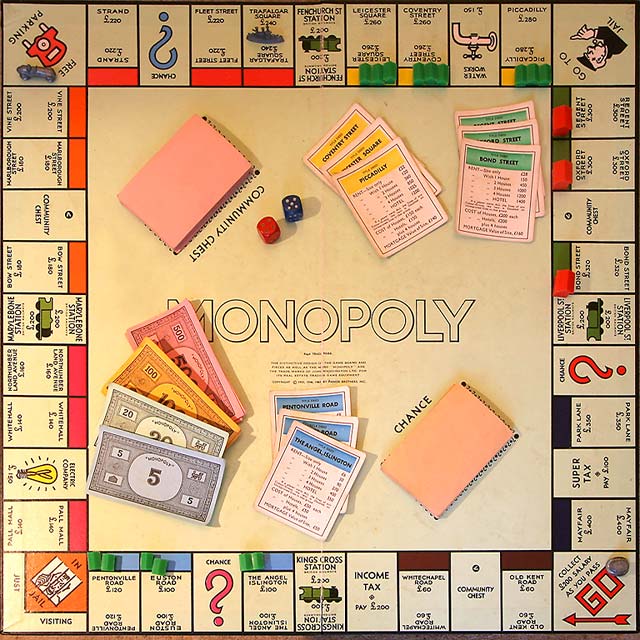

1. BURN: MONOPOLY / BUY: CHINATOWN

I’ve played Monopoly more than any other boardgame, and we all know the major design flaws, right? How it becomes clear who’s going to win some 30 minutes before the game actually ends. How, as the properties are sold, you have fewer and fewer decisions to make, until you’re just using the dice to generate random numbers and watching the game play itself.

It’s popular in the modern gaming community to rant about how egregiously shit Monopoly is, and though I have a certain amount of sympathy with that position, I think it’s important to acknowledge what it does right. After all, there must be some reason so many of us play it, beyond a kind of repressed self-loathing that demands hours of joylessly nudging a metal scotty dog round the perimeter of a square.

Deals. Doing deals in Monopoly is fun. Someone else has a property you want, you’ve got something they want, you’re competitors but you need each other, you’ve got these big wads of play money. It’s a great part of the game, negotiating with your enemy to get the properties you need to build a shitload of hotels and tax them out of the game. How do you convince someone to work against their own self-interest? That’s a good puzzle and a funny social dynamic, and it allows opportunities for really memorable interactions.

Luck. For the most part, dice rolls in Monopoly feel arbitrary and dull, but occasionally they create some great moments, like when you’re forced to run the gauntlet of Park Lane and Mayfair with hotels on them, and your little motor car is sitting there on Bond Street like a plucky little prairie dog about to dash out of his burrow under the shadow of a looming eagle, and you cross everything and roll and… land on ‘Super Tax’, which is apparently a thing. It’s either exciting or stressful, depending on your perspective, but it’s definitely engaging.

So look: what if I said you could have all of Monopoly’s cool deal-making and real estate haggling and empire building, plus all of the excitement of pressing your luck and gambling and riding the winds of fate, without the hours of tedious downtime, the late-game lull, and the dearth of meaningful decisions?

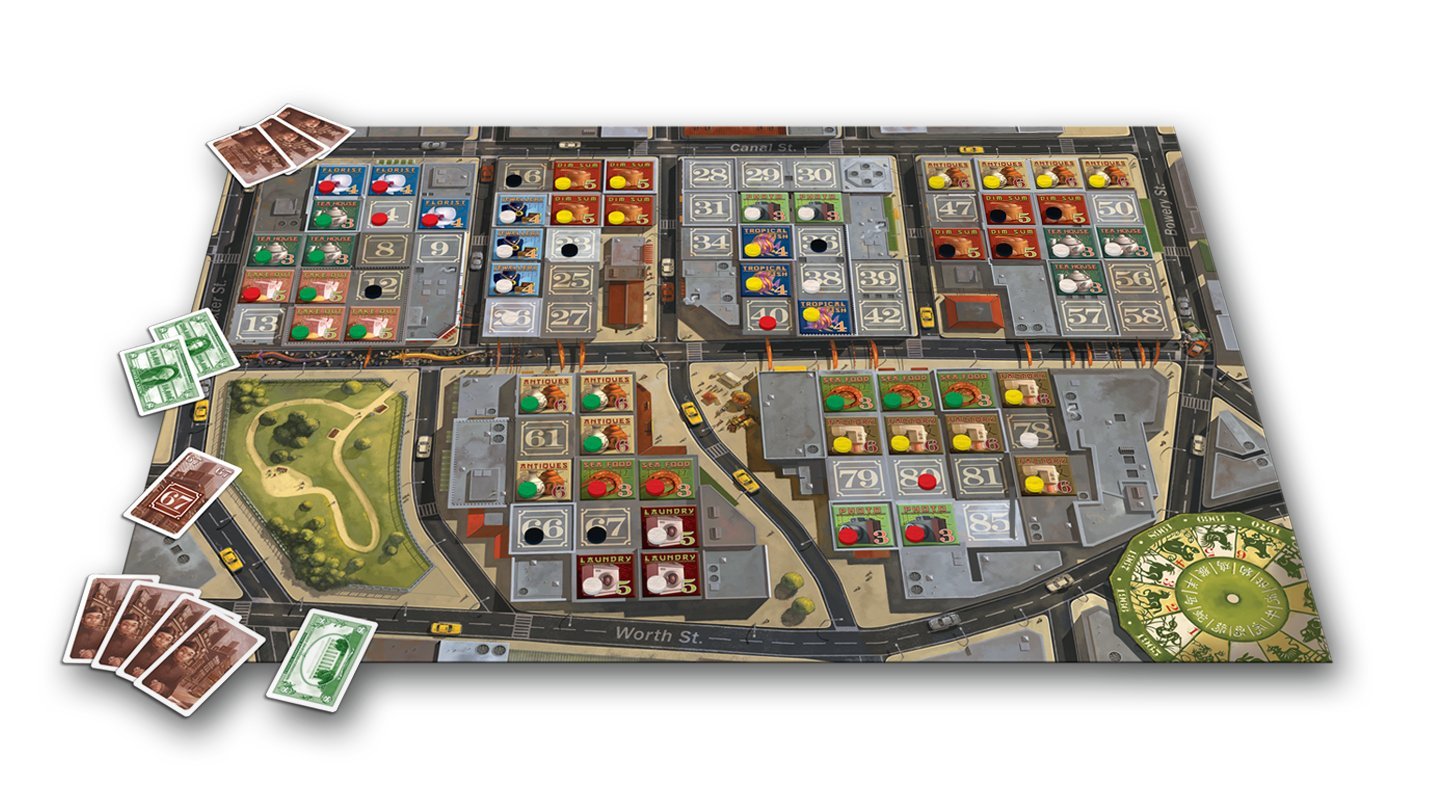

Chinatown is an awesome little real estate game set in 1960s New York where you and your friends compete to see who can create the most profitable business empire. It’s dead simple – much easier to teach than Monopoly, with all its fiddly un-mortgaging at 10% and rolling doubles to get out of jail – yet rich and challenging and really, really funny. Each turn you’re going to get some title deeds to parts of the city – you just get dealt them, no farting about rolling dice and paying money – and some businesses, like restaurants, pet shops, factories and camera stores. But to get the big money, you’re going to need your bits of real estate to connect up. So then comes the meat of the game – the deal making.

When I first heard about Chinatown it didn’t sound like my cup of tea. I like games that tell grand stories, and squabbling over Unit 17 didn’t exactly strike me as epic. But you’ll just have to trust me when I say it’s wonderful. At barely five minutes in, erstwhile lovely, retiring friends will be scheming, charming and browbeating one another into five-figure real estate deals with all the desk-pounding blowhard bullshit of Donald Trump, albeit with – one would hope – none of the batshit racism.

All negotiations happen simultaneously, meaning that players can undercut one another, jumping in on a deal just about to close, offering something better and freezing someone out. This leads to hilarious scenarios where someone draws a piece of real estate right smack dab in the middle of three other people’s business empires, and ends up receiving the other players like suitors as they all make their pitches as to why they can offer the sweetest deal.

And luck plays a wonderful, satisfying role in shifting the tides of the game. A plum plot of land one turn can become near-worthless on the next if other players draw the units surrounding it. Pull a couple of factory tiles out of the bag and suddenly you might be the only way your opponent can finish their big six-unit cash cow. Sometimes the person who rejected your advances the previous turn is forced to come crawling back to you, cap in hand, to try to charm a business out of you – and that’s really, really funny.

Oh, and you can lie. Any deals made on a turn are binding for that turn, but you can promise to furnish people with property or businesses later in the game and then basically screw them over. What I particularly like about the game is how players who do this never win. The other players end up cutting them out of deals in revenge, and so a short-term gain usually translates in your business suffering long-term – which again, feels great and thematic and appropriate.

Chinatown takes about 5 minutes to teach, and comes with little player cards that summarise how much each size of business is worth. The makers suggest it takes 60 minutes to play, but I reckon 90 is more realistic with the full 5 players, given how intense the negotiations get. The components are bright and the bales of play money add a nice feeling of grubby lucre to proceedings.

2. BURN: TABOO / BUY: CODENAMES

Here Taboo stands in for a whole genre of ‘guess the word’ games, including Articulate, Guesstures, Charades, Pictionary, etc. You know, where one person has to communicate a word or phrase whilst obeying some kind of restriction.

I don’t hate these sorts of games, per se – of course it’s entertaining to see someone try to frantically mime ‘donkey’ by giving themselves fake ears and silently braying, only for everyone to guess: ‘Demon! Raptor!’ Then they try to mime kicking like a mule and people shout: ‘Kung fu! Jackie Chan!’ Then they go for broke with ‘ass’ and the team are bemusedly yelling: ‘Bottom! Lost in Space! Ring of Fire!’ Still… eh. It’s weakly amusing, at best.

And I’m very aware that for some people, this can feel a bit like being publicly humiliated for the entertainment of the group. You’re up there, alone, clowning badly while people bellow nouns at you. You don’t always want that level of hopping about on Boxing Day. Also, you’re up there alone. It can feel quite isolating, and even I – a noisy extrovert – have sometimes felt my cheeks go all hot and my mind go blank as I attempt not to fail my team. Finally, these games tend to be a bit, well… manic. There’s a lot of shouting over each other and the actual ‘game’ portion is over very quickly, and often once you’re done and reveal the clue a team member will look annoyed and say ‘but I said that’ and you’ll be like ‘really?’ and they’ll be like ‘yes’ and you’ll be like ‘oh’ and so you just capered about like a gibbon for two minutes because of a communication failure. Which feels less amusing than it sounds.

Codenames has gone from being this game I heard excited whispers about, to appearing at almost every games night I go to. Its slim, sunburst maroon box is a welcome sight whatever the mood. It’s tense, it’s hilarious, it’s easy to teach, and it just creates great moments.

In Codenames, two competing teams of spies are attempting to make contact with their agents ‘out in the field’ without harassing innocent bystanders, inadvertently helping their opponents, or getting themselves killed. Both teams see the same 5×5 grid of 25 words – like SHARK, BEIJING, POISON – possible aliases your team’s spies might be operating under. Two team captains, or Spymasters, have access to a map showing them which code names correspond to which team, which are just civilians (and therefore worth nothing to either team), and which one is the deadly assassin.

The Spymasters take it in turns to give a one-word clue to their team, to help them find their agents. The one-word clue is accompanied by a number, indicating how many agents they want their team to try to guess this turn. So they might say TEETH: 2. Then their team know to look for two names that have something to do with teeth. So they might pick SHARK, or they might pick BRUSH, or they might pick SMILE, or maybe they’ll start being assholes and going ‘wait – a GEAR has teeth; oh, hang on – what about SALAD? Because spinach gets stuck in your teeth’ and you, the Spymaster, will be biting your fist and saying nothing because you’re not allowed to react or give any clues whatsoever, but SALAD is the assassin and you know if they choose that your team will lose the game instantly.

Whichever team finds all their agents first wins. I love Codenames. I liked the look of it when it first came out and, yeah. I worry about overselling it to people and putting them off so usually I just break it out and suggest we play without too much fanfare, and it sells itself. A super-solid, simple idea with loads of replay value.

It’s both fascinating and horrifying to hear team mates discuss how your brain works and what you would or wouldn’t associate with a particular word – kind of like unsolicited guerrilla therapy. Weirdly, although it’s a competition, you feel a real camaraderie with the rival Spymaster. They’re the only person who understands your anguish as your team mate’s finger hangs, Damoclesian, over the assassin while the group decides whether you meant PART or COMPOUND, and many have been the times when we hide our faces from the groups just so we can pull tortured grimaces at one another.

I love it. It’s much less of a catwalk for extroverts than Charades but loud, excitable groups will have a wonderful, raucous time arm-wrestling over clues and gasping at risky guesses. It’s sillier and more creative than Taboo, and more importantly the theme makes the stakes feel far, far higher, even though, at its core, Codenames is just a game about word association. It allows for real creativity and wonderful sideways logic, and the way you score means that – unlike similar games in the genre – the game is never over till it’s over. One team can always go for a final 5-word Hail Mary mega clue if they’ve fallen behind, and the leading team can always balls it up by accidentally picking the assassin when they’re just about to win.

This game is spreading, fast, and I suspect by next Christmas it will be a staple of many people’s boardgame collections.

3. BURN: CLUEDO / BUY: MYSTERIUM

For a game about murder, Cluedo feels oddly bloodless. It’s so dry that, when I played it again last Christmas, after a break of maybe 20 years, I couldn’t even remember how the game worked. I knew vaguely that I would, at some stage, be saying it was Colonel Mustard, in the Ballroom, with the Candlestick, but I didn’t know how I would come to that conclusion or – and this, I think, is the real kicker – why I should care.

And you know what – after playing, I wasn’t much the wiser. Cluedo is fine, sort of. You potter around this spartan top-down blueprint of what we’re told is a country house, walking into rooms and making baseless accusations, more or less at random. You don’t feel any investment in your guess because you’re just picking whichever room was nearest to you – you’re like an apathetic Keyser Söze, cobbling together an alibi about meeting a Mr Crest to play Dominoes because you’re lying amongst discarded pizza boxes and cans of super-strength lager.

And having to roll a die in Cluedo is unforgivable. It creates no tension whatsoever, just randomises your walking speed across a bland, symmetrical grid. So sometimes you can’t reach the conservatory for three turns because – what? Reverend Green has a sudden flare-up in his gouty leg? And then another player accuses you of murder in the library and you’re teleported there through the mystic powers of interbellum justice and the whole thing was a waste of time anyway.

Bolted on to this incoherent heap of gameplay mechanisms is quite a fiddly process of deduction based on elimination that, I admit, I struggle to get my head around. For me, it feels a bit too much like those logic puzzles you used to get in annuals that are all like ‘6 people of 6 different nationalities live in 6 neighbouring houses of different colours. Mr Wallace lives in the house with the blue door. The Frenchman lives on the end of the row. The green and red houses are not next to one another. Mrs Jones’ neighbours are Welsh and Greek.’ etc. It just feels like doing taxes, except without the motivation of avoiding a massive fine.

What I want is the feeling of solving a mystery. Cluedo doesn’t offer a mystery, it offers an algebra problem. It’s the most literal interpretation of Sherlock Holmes’ famous adage: ‘when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth’.

Mysterium does not eliminate the impossible – it embraces it. You know, one of the main flaws in Cluedo is that we don’t have any investment in the murder victim. He’s just a white cross on a poorly-rendered flight of stairs in the middle of the board. In Mysterium, the murder victim is the key player.

Mysterium is set in the 1920s in a haunted country mansion. Laird MacDowell, owner of the house and a gifted crystal ball reader, has gathered the most talented psychics from across the globe to help him exorcise the ghost that plagues his family home. However, when they arrive, the assembled mediums immediately discern that this spirit, although tormented, is not hostile – indeed it appears to be the ghost of a servant murdered decades before. Together, the mediums must work with the ghost to recreate the night of the murder, assemble a list of suspects, and then name the culprit so that justice may be done and the ghost may rest at last.

So, like Cluedo, you have a list of suspects, a list of rooms, and a list of objects. Unlike Cluedo, the artwork is beautiful. Absolute sex. Every illustration is lush and evocative, riddled with tiny details and brimming with mood.

Everyone is working together – the psychics, and the murdered ghost. So it’s easy, right? The ghost goes ‘it was her, there, with that’ and everyone claps and you all go home.

No, you twonk. As any long-term fan of Derek Acorah et al will know, ghosts aren’t able to send clear, coherent messages from the spirit realm. Instead, they transmit vague intimations and flashes, weird images dredged from the medium’s subconscious that hint at the spirit’s true meaning. Thus, as the ghost, your only means of communciating with the psychics is by sending them bizarre visions via a deck of surreal picture cards which you draw from each turn. As the ghost, you have to choose which of these dreamlike visions – a rat wearing a top-hat, a chimney sweep riding a penny farthing through the air over a town while suspended from balloons, a figure weeping at a crossroads, etc – might hint at a particular suspect, location or object you need to steer each psychic towards.

If the psychics succeed in recreating a shortlist of suspects, matched with the locations the ghost remembers them in and the potential murder weapons they touched, play proceeds to a final round in which the ghost at last recalls who killed him, and gives the group a shared vision pointing them towards one of the combinations of culprit, location and murder weapon. Psychics who have performed better with their predictions during the seance get to see more of the vision before secretly voting on who they believe the murderer to be. If a majority of psychics pick the correct culprit, the game is won. If not, the ghost vanishes, his soul still restless.

THIS GAME IS FUCKING GREAT, YOU GUYS. Caveat: to get the most out of it, players need to be prepared to get into the spirit – oh ho – of it. It’s not the sort of thing to play with the football on the telly in the background and people checking their phones or getting up to put the roast potatoes on. We played our first game in a darkened room with a crackling log fire, with the ambient soundtrack provided by the game’s makers, Libellud, playing in the background and the ghost communicating only through a ‘spirit drum’, a big floor tom my wife uses in her band, with one boom for yes, two booms for no. The players all got into character as numerologists, pendulum dowsers, I-Ching diviners and tarot readers, sustaining accents of varying authenticity for the entire game, even appropriating a globe lamp as a crystal ball.

I don’t think most people need to go that far, but it definitely rewards a bit of mood lighting, and players who are prepared to focus for the duration of the game. The box says the game takes the bizarrely specific playing time of 42 minutes, but I reckon 90 minutes is more realistic – including rules explanation our game definitely took 2 hours.

I played as the ghost, and it was definitely an intense experience, desperately trying to cobble together some kind of coherent message out of recondite surreal bullshit – but hugely satisfying when a psychic made a sideways connection between the images I sent them and the suspects in front of them, linking – for example – the coffee cup beside the policeman suspect with a coffee ring in one of the images, or spotting how the hooks along the top of one vision matched the hooks that cuts of meat were hanging from in the larder. We played with the full 6 players and decided to jump straight in with the medium difficulty setting, rather than the easy version the rulebook suggests, and we just managed to squeak a win.

I don’t know how the game holds up to repeat playings, whether certain cards or combinations of cards become familiar, or whether each new ghost brings a different set of bizarre mental associations to the images. You don’t have much control over your hand of picture cards, as the ghost, so you have to try to make links where you can – inevitably some psychics end up with much ropier, vaguer visions than others! But this is part of the fun – indeed, you really feel like a frustrated spirit, unable to get your message across, desperately trying to nudge the players towards the truth. Each time someone correctly identified a suspect, location or object, a big cheer went up round the table. It really felt like an adventure.

If Mysterium sounds like a good fit for your family, I heartily recommend it – with the one warning that, at the time of writing, it is sold out almost everywhere in the UK. Everyone is buying it because it’s brilliant. Ring round your local gaming shops, and if you can, reserve a copy. There’s really nothing like it.

4. BURN: RISK / BUY: GAME OF THRONES

Risk is very dear to some people’s hearts – generally people who haven’t played it in at least 10 years. We tend to forget how it could drag on, how badly Risk suffered from ‘runaway leader’ syndrome, where the winner becomes obvious well before the game is officially over, how drawing bad start positions could basically lose you the game before you began.

But – lest I start to sound like a boardgaming hipster, cocking a snook at anything with a whiff of popularity – let us salute Risk for what it succeeded at. Amassing huge armies on your neighbour’s borders feels very, very exciting, and in that first moment where you go on the assault, swarming into the juicy peach of their territories like so many ravenous ants, you feel powerful and they feel appalled and it’s good fun. Then the next turn, when your opponent gets reinforcements and they see you’ve spread yourself too thinly and they come steaming back into you and claim all those territories back and more, that’s fun too. You’re punished for being greedy, and you don’t feel ripped off, you feel like it’s poetic justice and that’s a great experience for a game to provide.

But still. For the most part, Risk feels arbitrary and imprecise and vanilla. You don’t have much investment in your territories or armies, you can’t really do deals or truces except in the most rudimentary ‘please don’t attack me this turn’ sense, and one little plastic soldier is the same as another. Who are you? Why are you fighting? Why are your forces randomly distributed across the globe in small pockets? When would that ever happen?

Now – I didn’t believe it when someone first told me that the Game Of Thrones boardgame was good. I haven’t watched the show or read the books, but I was pretty sure it would just be a shitty cash-in that leveraged dumb fans’ brand loyalty into shifting tat for £££s. The repackaged Lord of the Rings version of Risk, or the Pirates of the Caribbean reskin of Waddington’s Buccaneer, or, indeed, Star Wars Monopoly, all set the bar so incredibly low for licensed tie-in boardgames that the bar is basically at the bottom of a marine trench, crushed into a kind of egg by the water pressure.

But it’s everything you’d want it to be: a big, backstabby wargame where the different houses are all trying to defeat each other not only by conquest on land and sea, but via political intrigues and pragmatic alliances. I don’t have any interest in the lore of GoT nor the various characters, but it was impossible not to get caught up in such an epic battle across Westeros for the Iron Throne. Each turn you secretly place orders on units, meaning everyone decides simultaneously – there’s a lot of tense gambling here, as you try to read your opponents’ intentions. Did they just put down an order to march into your territory and attack your castle with their siege engines? Should you order your troops to defend? But if you do that, you can’t collect taxes and harvest food from that territory, which you need to wield political influence.

The influence track is one of my favourite bits of GoT. Every so often, players have to participate in blind bidding to determine their positions on the game’s three influence tracks, broadly representing political power, martial prowess and espionage respectively. Ending up on the top of these tracks gives you a massive advantage over your opponents – but your dominance might only last a turn before things change again, and if you get too powerful the other players may band together to wipe you out.

Another lovely marriage of game mechanics and theme is the ever-present threat of the Wildlings building up in the north. Each turn, more and more nasties gather in the north, preparing to attack. Working together, the players can easily take them on. All you have to do is get the various houses cooperating selflessly for the good of Westeros.

Ah. Yeah, so most of the time you’ll painstakingly broker a truce to face the Wildlings threat then one backstabbing little shit will pull out at the last minute and everyone loses the resources they spent and loses the battle and yes, that backstabbing little shit is usually me.

You absolutely don’t need to like or watch GoT to enjoy this game – I’m proof of that – although I daresay encountering your favourite characters and using them as generals in battle slathers a nice saucy layer of narrative white sauce over the waiting lasagne sheets of strategic combat. One itty-bitty proviso: the game definitely works best with the full complement of six players. With less, it can feel slightly skewed towards players whose territory borders on neutral land, which is fine if you’ve got some less experienced or younger players who you want to give a boost to, but feels a bit unsatisfying if you want an asymmetrical-but-balanced war experience.

PS: if you want a war game but there’s only two of you, rather than trotting through Risk’s shitty two-player variant, buy Twilight Struggle. It’s a game of global conflict set across the entirety of the Cold War, there are coups and espionage and the real danger of the game ending in a worldwide nuclear holocaust, and you learn a bit of history while you play. When I played with my Dad my Mum had to come in and remind us to sit down, because we’d been standing for over half an hour straight, right next to our chairs, desperate not to mix some essential detail of the global political situation. It’s excellent.

5. BURN: THAT CRAPPY 5000-PIECE JIGSAW / BUY: CARCASSONNE

I understand the appeal of jigsaws, in the same way I understand the appeal of watching a food mixer chop breadcrumbs or following the wiggly pattern in a carpet as if it were a maze to see if you can get all the way to the skirting board and ‘escape’. Still, if I’m going to veg out I want to fall into it accidentally, not make an afternoon-long activity out of it.

If you want to build a lovely thing and relax while you’re doing it, Carcassonne offers a far richer, more fun experience. Build a medieval empire in southern France and populate it with little wooden people! Look, there’s a river, and a city, and monastery, and a little abbot tending a flower garden. And I just connected my road with yours and robbed you of 8 points and now you’re furious with me. That’s the gentle experience Carcassonne offers.

It’s a simple game for 2-7 players where you pick tiles at random from a stack. Each tile has a bit of landscape on it – a bit of city, or road, or river, or maybe a monastery – perhaps several of those things. All you have to do is pop it down on the table next to a tile the landscape joins up with – so connecting a road to a road, or a city to a city, or whatever. Then you get to pop one of your little wooden people – called meeples – down on the tile you just placed. Every time you complete a piece of terrain, like a city surrounded by walls, or a monastery surrounded by land, you get your meeple back and score points. That’s it.

Carcassonne is very simple and a great game for people who don’t usually get on with games. It’s not too competitive and there’s some luck involved but it’s not brainless either – you definitely notice yourself getting better after a few games, making shrewder choices with your tile placements, holding back meeples when you’re running low. Most games that say they’re for 2+ players don’t really hit their stride until 4 players are involved, but Carcassonne makes for a really nice, low-intensity two-player game as well as an enjoyable, mildly strategic 4 or 5 player game. There are metric tonnes of add-ons and expansions in case you want a bit of variation, but the core set has enough to keep most people going for years.

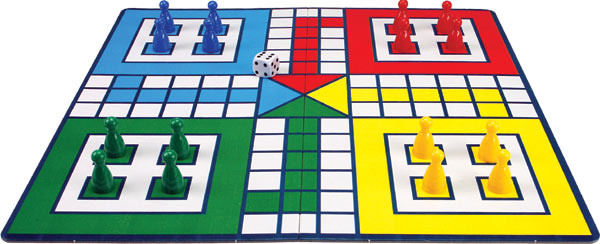

6. BURN: LUDO / BUY: SURVIVE – ESCAPE FROM ATLANTIS

Ludo is the worst. It’s the absolute pits. I maintain that no one has ever experienced joy or even mild amusement whilst playing Ludo. It projects a suppressant field that prevents all pleasure. If you really must have your fix of arbitrarily shunting tokens round a board to satisfy the whims of a die, at least introduce the possibility of having your grandmother feed you to a shark while the rest of your family laughs and applauds.

In Survive – Escape From Atlantis, you and your friends’ little meeples are trying to escape from the island of Atlantis as it sinks into the ocean. Rising out of the waters are sea monsters, sharks and whales who will capsize your boats and gobble up your meeples. Can you reach the safe isles at the edges of the board before the island’s volcano erupts and the final mountainous regions sink beneath the waves?

Each player controls a different colour of meeples, but – just like in real life – the value of each person is determined not by the colour of their skin but by the big number painted on their bottom. Big numbers are carrying more treasure and are therefore worth more to you if you manage to get them home safely. In a neat twist, you’re not allowed to look at the number once you’ve placed each meeple on the board, meaning you need to try to remember which of your meeples are the high value ones and which you can safely sacrifice to the kraken.

SEFA is really silly fun. Each turn you move your meeples a total of 3 spaces, remove a tile from the sinking island, and roll a die that lets you move either a whale, a shark or a sea monster. Maybe you’ll move a sea monster farther away to leave a clear route for your boat to reach the shore. Maybe you’ll swim a shark into one of your opponent’s meeples who has fallen into the sea and gobble them up. Luck plays a big part but so does the revenge and taking big risks – each game tells its own little story, it’s easy to learn and the components are colourful and great.

Well, now you’ve got me all excited about Codenames and Mysterium, only to find that they are rarities and cost ££££££££££££s… Gissa lend?

Mysterium is definitely hard to get hold of at the moment Emma, especially online, where there’s quite a bit of confusion between the Polish original and the (I think much improved) English version. But Codenames is everywhere and will cost you about 12 quid!

Best games I have found are (1) Pazazz, in which you have to think of things beginning with letters of the alphabet. It is simple and can be played individually or in teams of two or more, and it can be hilarious as people try to get away with things “I always take zabaglione on a picnic”. I’ve never met anyone who didn’t enjoy it. Unfortunately it has to be bought second hand on ebay, but there are usually some around. Be sure to get one with a fully functioning timer. (2) Rapidough – like pictionary but modelling with play dough. (3) Telestrations – a kind of sketching chinese whispers game which is all the more funny if people can’t draw well. All three are entertaining and funny as well as being short!

Loading @Scenario in Dalston, on Stoke Newington Rd. has Codenames, Mysterium (and Cluedo), Carcassonne, and I think GoT – all free to play. Turn up, buy a drink (20+ video game themed cocktails) and play a table-top game with your mates for a few hours.

4. BURN: RISK / BUY: GAME OF THRONES

These two games, while they seem thematically the same, they are very, very different. Risk 2210AD is far more of a “BUY” as it has far more theme to it, variety of gameplay, and adds just more to the stale base game. Also time wise and rule wise it is easier to understand. 2210AD is played through a 5-Year period (5 turns per person) where games tend to last around 3 hours with all 5 players. GoT will take at least 5+ hours with all 6 players, hell I’ve played games with 4 players lasting that long due to the obscure long winded rules.

http://www.leisuregames.com/ Based in Finchley Central, London.

Has Codenames for £13.99

Ticket to Ride

Pandemic

leisuregames are all out of Codenames. So is every other small indy retailer I have just spent the last hour searching on…..

I don’t agree wit burn Risk for GoT.

Having obsessively played the GoT when it first came out (with 6 players) there is a distinct lack of game balance – playing as certain factions it is significantly easier to win.

Hey Jo – I agree that Thrones is definitely asymmetrical. But then – Risk *always* gives some players easier starting set ups, and going first is *always* a distinct advantage. So heavy inequalities are baked into the game design. With Thrones, some houses tend to do better than others (although, as with Twilight Struggle, these apparent advantages lessen the more times you play, as you learn to pursue multiple paths to dominance) but, unlike Risk, that isn’t random, it’s explicit and it’s supported by the theme. You can assign players based on who wants a challenge – indeed, you can bid for sides. I don’t think asymmetry reflects inherently bad game design, as long as the players are aware of it. It’s okay for some players to have a harder task, because the glory of succeeding is greater too. It adds longevity by offering a variety of game experiences.

Thanks very much for recommending Codenames – we took it to the annual 3-day New Year party and two families loved it so much they ordered it the morning after the games! Brilliant fun, very easy to pick up, and only 10-15 minutes per game. What’s not to like?