BBC4 are starting a new season called Why Reading Matters. Reading and literacy are Good Things, I think we all agree. But it was a line in the Radio Times, previewing the season’s launch programme, where ‘Children’s Poet Laureate’ Michael Rosen ‘does for literacy what Jamie Oliver did for school meals’, that thumped one of my hot buttons.

The second paragraph begins: ‘Seeing the children turn their attentions from computer games to We’re Going On A Bear Hunt is uplifting stuff…’

Aw… c’mon now. Why did you have to bring games into this? What did they ever do to you?

First off, I ought to make it clear that I’m a big fan of Michael Rosen. Specifically, I grew up listening to a tape of his book Hairy Tales and Nursery Crimes, and I loved it. Hairy Tales and Nursery Crimes is just about the most puerile exercise in storytelling imaginable. The premise underlying the book is that he retells classic fairytales, substituting some of the words for ones that sound similar – thus the Giant’s cry of ‘Fee Fi Fo Fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman’ from Jack and the Beanstalk gets changed to ‘Fee Fi Fo Fum, I smell the blood of an English bum’. As you can imagine, at seven, this is hilarious. In fact, it still makes me laugh today.

Part of the reason I loved it was the pointlessness of it all. I mean that in the best sense. So often, children’s books are expected to be worthy and elucidating, or beautiful, or intelligent. Even Roald Dahl, so often held up as hilariously subversive, was usually trying to convey broader moral ideas. But in HTaNC, there was none of that. The point, if anything, was love of language. What would have been the Giant’s castle is a ‘car sale’. There’s no logic behind it, except the two things are almost homonyms, and, well, it’s quite funny.

Anyone who’s had the misfortune to get stuck in a long conversation with me will know I still enjoy this arbitrary word-switching today. As a kid, it was nothing short of liberating to be told – albeit implicitly – that it was okay to love language for language’s sake. It taught me the power of words, showing me how simple tweaks of a vowel sound could radically alter your fictional landscape.

For me, that was true subversiveness. I’d spent countless hours sat cross-legged in assembly, singing words to hymns written in red marker on a OHT projected onto a screen in front of us. Nobody ever explained what the songs were supposed to be about, or why we were singing them, or demonstrated why we ought to believe in God, and even then, something about the bland conformity of it all bothered me. Actually, that makes me out to be more of a rebel than I was; I don’t think I had a problem with conformity – I would’ve dearly liked to have fitted in – just blandness. Thus I began to amuse myself by substituting words in the hymns. I’m sure lots of people did this when they were younger. Some substitutions were, I think, fairly canonical, practised in schools right across the country – ‘I am the Lord of the Dance said he’ getting changed to ‘I am the Lord of the damp settee’, for example – where as others were entirely my own invention, and, like Michael Rosen’s handiwork, totally pointless – except for the fact that they amused me, and allowed me to wrest back a few crumbs of self-expression.

All of which, I expect, would be duly lauded by the UK’s self-appointed doyens of literacy as more proof – as if proof were needed – of the efficacy and magical transmogrifying powers of reading, and yet another reason why they should be paid lots of money to announce to people, in a variety of ways, that reading is a Good Thing.

But the fact is, video games had as much of an impact on the pupal Tim Clare as reading, if not more.

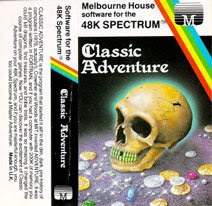

For a start, the two are far from mutually exclusive. Most games require basic literacy skills to enjoy, and many are so text- or dialogue-heavy as to be impenetrable to someone without a significant fondness for reading. The limited graphical capacities of the ZX Spectrum meant that most of the games I grew up with relied on a combination of text and imagination to construct their fictional universes, but unlike books, the reader played an active role in exploring the world and pushing the story forward.

As technology has progressed, so too has the sophistication and grandeur of the worlds games evoke. Even a decade ago, we saw titles like Planescape: Torment, a rich, funny, elegaic parable about a man who cannot die, and who cannot remember who he is.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mgqX82-HRYE]

It came out a full year before Momento, but the similarities are uncanny, despite the former’s being set in a Fantasy universe where continents are shaped by the morality of their inhabitants. The central protagonist has no memory of his past, but has covered himself with various tattoos which give him clues – even the disembodied skull, Morte,

who joins him as a sidekick, sounds oddly akin to the manipulative Teddy from Momento, and proves to be similarly untrustworthy. The game has multiple endings, over a hundred minor characters, and, it’s estimated, in excess of 800,000 words of text and dialogue.

who joins him as a sidekick, sounds oddly akin to the manipulative Teddy from Momento, and proves to be similarly untrustworthy. The game has multiple endings, over a hundred minor characters, and, it’s estimated, in excess of 800,000 words of text and dialogue.

But even games like Super Mario – which has only two pieces of dialogue: ‘Thank you, Mario, but your princess is in another castle,’ and, I believe I’m right in saying, ‘Thank you Mario. Your quest is over. We present you with a new quest,’ – fired my imagination in ways nothing else could. I was dazzled by the bright colours, the impossible worlds, the excitement and creativity and otherness of it, and best of all, they were all worlds in which I had control.

When we wrote the full version of Infinite Lives, our show about art, video games, and growing up, Joe Dunthorne told a story that really resonated with me, about coming downstairs on Boxing Day, having spent two days holed up in his bedroom battling aliens on Turrican 2, and trying to convey his excitement to his family. Of course, he got a well-meaning but indifferent ‘That’s nice dear,’ and he felt so deflated, he had a little cry.

When we wrote the full version of Infinite Lives, our show about art, video games, and growing up, Joe Dunthorne told a story that really resonated with me, about coming downstairs on Boxing Day, having spent two days holed up in his bedroom battling aliens on Turrican 2, and trying to convey his excitement to his family. Of course, he got a well-meaning but indifferent ‘That’s nice dear,’ and he felt so deflated, he had a little cry.

I remember some relatives coming over from Canada when I was no more than 8 or 9, and my parents bringing them into my room, where I was playing a demo of a game whose name escapes me, but it was a pretty obscure vertically-scrolling shoot-em-up where you piloted some kind of biplane, everything was blue monochrome and almost half the screen was taken up by the score bar, which had a picture of some kind of dog wearing flying goggles at the top of it. That doesn’t really help you much, except to give you an idea of how vivid and real these games were to me – much more, at least, than these ‘Canadian relatives’, whose names, faces, and exact familial link to me have all burned away like so much morning fog.

‘Look at this,’ I said. ‘I’m playing a game.’

The chap gave me an awkward smile and said: ‘That’s nice. But we’d really like to hear you play on your fiddle.’

I hated playing the violin. I only took it up because I’d asked my Dad if I could take guitar lessons, but there weren’t any places left, so my Dad told me to do violin, because ‘it’s almost exactly the same as a guitar’. I ended up wasting four years doing lessons on an instrument I never practised, whose music I never listened to, and when I told my music teacher Mr White I wanted to give up, I felt so wretched and guilty that I sobbed.

‘This game is really cool,’ I said.

‘Could we hear you play your fiddle?’ said the relative.

I was so deflated. We’re constantly told that video games make kids sullen and uncommunicative. But, until now, at least, most adults are utterly ignorant of what a game can be, and how it can feel to immerse yourself in these rich, diverse fictional worlds. They don’t have any shared vocabulary or common experience with which to chat to their children about video games.

I am now the obligatory weird guy on the train who gets talking to strangers’ kids. It’s because I’m usually playing my DS, and every so often, a child will sidle up to me, trying not to look like he’s bothered, but surreptitiously looking to see what I’m playing. Then, he or she will try to start a conversation, either with an attempt to impress me by how many Pokémon they’ve caught (this is an impossible task – I have 423 Pokémon and counting, including Mewtwo; my Pokédex belongs in the British freaking Library) or with a question about whether I’ve played such-and-such a game.

I am now the obligatory weird guy on the train who gets talking to strangers’ kids. It’s because I’m usually playing my DS, and every so often, a child will sidle up to me, trying not to look like he’s bothered, but surreptitiously looking to see what I’m playing. Then, he or she will try to start a conversation, either with an attempt to impress me by how many Pokémon they’ve caught (this is an impossible task – I have 423 Pokémon and counting, including Mewtwo; my Pokédex belongs in the British freaking Library) or with a question about whether I’ve played such-and-such a game.

Just taking the time to engage these kids in normal conversation about the games they like reveals a complex level of imaginative and intellectual engagement. They’ll chat enthusiastically about the characters they’ve met, the adventures they’ve had, their triumphs, their failures – they’re far from dimwitted automatons. They’ve just learned that adults don’t care about these things, and they don’t enjoy revealing their enthusiasm only to have cold water poured on it.

What if a child came downstairs brandishing a paperback, exclaiming: ‘Oh Dad, I just read this amazing book!’ and the father rolled his eyes and said: ‘That’s nice. Hey, would you put that down? We want to see your penalty kicks.’ I mean, there’s nothing wrong with expressing yourself through sport, either, but isn’t it right that we encourage our children’s passions? (unless they’re fond of crack, or something)

Video games are a fantastic opportunity. Rather than trying to prise joypads from children’s enraptured grasp, we need to shed all this pig-ignorant stuffed-shirt prescriptivism and adapt our education system to reflect genuine interests and needs. With not even 5 hours a week, but just 5 hours a term for every child, spent on encouraging ways in which they can critically and creatively engage with interactive media, we could lever disproportionately grand benefits to hundreds of thousands of children’s intellectual and artistic development. Poets with books to flog may huff and puff about children reacting with indifference, but it seems to me that if you want to establish a dialogue with people, it’s only polite to find out what they’d like to talk about.

Kids are going to play video games whether ill-informed pundits like it or not. Gaming has been with us for almost three decades now. We need to recognise this as the opportunity it is. Gaming is no more shameful than reading. When will educators grow up?